The journey from the small Eldoret airport to the town of Iten, in southwestern Kenya, takes about an hour. It is an unlit winding road with few road signs: you need to know where to get there. The city’s population is not known – there has been no census for more than a decade – but the local City Council estimates it at about 56,000 inhabitants, up from 40,024.

About 35% live below the poverty line. And yet a sign on the only paved road leading to the city calls it the House of Champions because of its phenomenal sporting successes. This corner of Kenya has produced 14 men and nine women winners of the Boston Marathon since 1991, winning 22 and 14 respectively. They have also won 13 of the 18 gold medals in the 3,000-meter steeplechase at the World Athletics Championships since the event was introduced in 1983.

Nearby, in Kaptagat, a rural town less than an hour’s drive from Iten, some of the fastest long-distance runners in the world live and train. These cities are similar. Life here is simple; there are few distractions, running is revered, the long clay roads offer perfect treads and, at an altitude of 2,400 meters, they offer ideal training conditions at high altitudes. But these conditions cannot last.

Throughout East Africa, the most obvious climate-linked dangers are drought, extreme heat, Overflows in some regions and the resulting loss of biodiversity. According to Professor Vincent onywera, vice-chancellor of research, Innovation and public relations at Kenyatta University, who has studied Kenyan runners for most of his professional career, the climate crisis could seriously affect health issue trends and performance. “I expect injuries to increase as the drought makes the clay roads harder than the pavement and the impact on the knees and hips takes its toll.”

Athletics Kenya President Jackson Tuwei is worried about more than the peril of health issue. He is worried about the participation as a whole. “If the young athletes are hungry, they won’t run. If the air quality is bad because it is dusty and smoky, don’t run. If there is no shade because the trees have been cut down and there is no water to drink or take a shower, don’t run.”The drought will cut off the Pipeline of athletes in Kenya if solutions are not found soon.

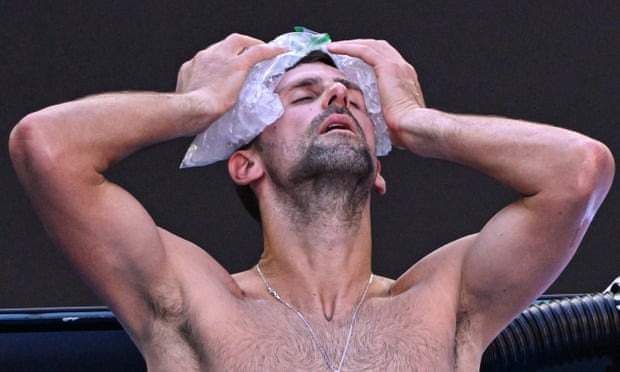

The heat makes everything worse. Tuwei called this his first concern for Kenyan athletes. “When we run during the day, it can be extremely hot and therefore sometimes we have to change our programs to run in the evening or very early in the morning. We have experienced high temperatures here in recent years, which has forced us to change our event schedules.”

Sleep is another victim of the heat. Onywera stressed that a healthy sleep schedule is essential for runners’ success, but that heater nights across the country are changing performance results for some. “You can see the effects of the heat at night. Concentration decreases, Motivation is low, energy level is low.”

Athletics Kenya is worried about how the climate crisis is shaping the future of her country, not to mention her Sport. And yet, a country like Kenya cannot do much to improve its climate performance, because it accounts for 0.05% of global emissions. Even if significant emission reductions are achieved, this will hardly move the needle. Athletics Kenya is therefore choosing a different path: to train its elite athletes – some of the most visible people in the country – to become spokespersons for the climate emergency.

“When our riders come out and do well,” Tuwei said. “We want you to also talk about the environment, because it affects us here, it affects you and maybe people are listening.”

Pakistan, another former British colony, faces other challenges. The summer of 2022 brought devastating Overflows that killed almost 2,000 people and caused billions of rupees in damage and losses. The Overflows have been blamed on a toxic cocktail of glacial melt – Pakistan has most glaciers outside the polar regions – and heavy monsoons, both linked to the climate crisis.